3 Current and future applications of AI in Earth-related sciences

In this chapter, we concern ourselves with some present day and possible future use of AI in scientific disciplines, mostly relating to the Earth system, including individual disciplines studying particular aspects of the planet, such as the atmosphere, the hydrosphere, the biosphere, the cryosphere, the lithosphere, etc., as well as Earth system science. However, we also consider technical sciences, which produce the myriad Earth-relevant datasets, obtained both through in situ observations and through remote sensing, as well as other disciplines from which inspiration can be gleaned concerning the productive use of AI.

3.1 Summarization and dimensionality reduction

Methods for summarization and dimensionality reduction have long been used in the sciences in order to reduce a complex data landscape to a more tractable level. This includes mathematical and statistical techniques such as singular value decomposition (SVD), and principal component analysis (PCA). AI and machine learning methods are increasingly being applied in the pursuit of this same objective. For example, machine learning has been used to produce a map of the ocean’s physical regimes. A classical clustering algorithm known as k-means was applied to a dataset of physical quantities characterizing sea water dynamics, such as surface and bottom stress torque, bottom pressure torque, etc. This produced five clusters, corresponding to geographical areas with distinct physical regimes [26], [27]. Such a process allows researchers to distill a complex dataset down to a handful of patterns, which can each be studied in greater detail.

This use case is bound to continue and be built upon with newer ML techniques. For instance, a more recent algorithm based on deep learning can be applied towards the same end; the t-SNE [28] deep learning technique, in combination with a data mining algorithm called DBSCAN, was used to obtain a map of oceanic ecosystems [29], [30]. This two-step methodology is illustrated in Figure 3.1.

![Marine eco-provinces mapped with machine learning. Left: t-SNE projection into a 3-dimensional space of the data set. Right: Spatial representation of the clusters obtained through DBSCAN (color indicates cluster ID) [30].](images/sonnewald_ocean_eco_clusters/ocean_clusters_combined.png)

Figure 3.1: Marine eco-provinces mapped with machine learning. Left: t-SNE projection into a 3-dimensional space of the data set. Right: Spatial representation of the clusters obtained through DBSCAN (color indicates cluster ID) [30].

As discussed throughout this book, the traditionally preferred approach is to use a simple method whenever possible. In the context of identifying clusters in data, the clusters are then more interpretable than if a black box algorithm is used. However, in some cases, complex methods yield better results, so the question is perhaps akin to the military question of asking whether a map obtained from an enemy is preferable to no map at all. Researchers must judge which tradeoff between utility and interpretability is appropriate in each particular use case.

It should also be noted that AI can serve as scaffolding, to explore a dataset, and eventually be replaced by a more principled analysis. This could become an increasingly widespread modus operandi, as forays into explainable and interpretable AI techniques generate useful and portable tools. For example, consider the concept of saliency mapping, which allows the user of a convolutional neural network (one of the most prevalent deep learning variants in image processing, cf. Section 2.10) to inspect which areas of an image were predominant in determining the model’s output. The most common saliency mapping technique at the time of writing is called layer-wise relevance propagation (LRP). The saliency map obtained by LRP in the case of a generic image classification example is shown in Figure 3.2. Although this technique is not fully robust (for example, it is not immune to adversarial attacks with images doctored specifically to deceive the model [31]), it can nevertheless provide some insight into the model’s ‘thinking’, and thus provide the user with information upon which to judge its validity. LRP has been used in the context of investigating physical causes of climate change with ML. For instance, two Stanford researchers set about detecting the circulation patterns of extreme precipitation in images of 500 mb heights and of sea-level pressure, using as labels the observed precipitation data from stations, and PRISM precipitation data. They relied on LRP to get deeper insights into their model’s mechanics [32].

Figure 3.2: Layer-wise relevance propagation (LRP) applied to the image of a rooster (left). The neural network correctly classified the image, and LRP (right) reveals which regions in the image were the primary influences to arrive at this classification; telltale features like the bird’s comb and wattle are highlighted. Original photograph by Simon Waldherr (CC-BY), processed through http://heatmapping.org.

3.2 Compiling datasets

The most successful application of deep learning has long been in the supervised learning setting (cf. Section 2.2), in particular for the image classification task, or variants thereof. The task amounts to determining the contents of an image. This is being applied to a plethora of research problems, such as tracking layers of ice in icesheets based on radar images [33], detecting the thawing of permafrost [34], identifying storm-signaling cloud formations such as the Above Anvil Cirrus Plume [35], or counting trees in the Sahel [36]. AI is indeed becoming a widespread tool among scientists, and scientific organizations are taking steps to integrate it into their processes. For example, NASA aims to increase the utilization of its image archive, by implementing ‘search by image’ functionality. This could enable researchers with a research question in mind, but initially having only a small data sample available, to assemble a larger dataset for study. Based on a relatively small set of exemplars supplied by the user, the system is designed to comb through the image archive, and extract image patches that bear a sufficient resemblance to the exemplars [37].

In each of these applications, AI acts as an identification mechanism for phenomena of interest, to be studied further by the scientists. Like an archaeologist’s shovel, it helps us unearth finds. However, it may entice us to dig where the ground is softest, or allow us to mostly find objects that are buried shallowest. In other words, it can introduce biases. Understanding and handling such biases remains an important open problem. There is active research on using methods with increased explainability, such as Topological Data Analysis, applied e.g. for finding atmospheric rivers [38].

On a related note, machine learning methods for ‘information fusion’ are being explored very actively in the field of Earth observation, to merge data originating from a wide variety of sensors, stations, and model simulations [39]. Combining deep learning with process-based approaches for Earth System Science has been recognized as an important challenge [40] and is an active area of research.

3.3 Surrogate models

Many processes of the Earth are very expensive to simulate, especially at fine resolutions. This is a crucial issue in climate modeling. Processes such as cloud formation and dynamics have significant effects on the warming of the tropical oceans; however, they occur at spatial scales that are orders of magnitude smaller than the width of a grid cell in even the most powerful climate models; on the largest supercomputers, the latter only operate on a grid with a spacing measured in kilometers, whereas the behavior of clouds requires going down to meter scale, or even much smaller if cloud nucleation physics is considered.

Assuming that computers keep improving at historical rates (more on this in Chapter 5), we could see global climate models resolving low clouds by the 2060s [41]. In the meantime, climate modeling makes use of parametrizations for these subgrid processes. Rather than simulating physical first principles, a parametrization provides an approximation of the processes, fitted on empirical or simulated data. The same goes for numerical weather prediction, where relevant processes that are often parameterized include shallow and deep convection, latent and sensible heat flux, turbulent diffusion, wind waves, etc [42]. AI/ML models can be used in this way, and are increasingly being modified so as to incorporate physical constraints [43]. Accurately representing convective processes in climate models while retaining interpretability, is an active area of research, and some studies attempt to recover low dimensionality by using encoder-decoder architectures, with a parameter bottleneck in the mid-section of the model [44].

More generally, AI lends itself to surrogate modeling, when an outcome of interest cannot be easily measured or calculated. This can be useful in the case of parameter exploration – if a simulation is expensive to perform, parameters should be carefully selected, which can be assisted by a much cheaper surrogate model. Surrogate models are also seeing increased interest in forecasting applications. The AI4ESP workshop mentioned in Chapter 1 identified forecasting and understanding convective weather hazards as promising application areas, such as in the case of tornadoes [45], wind, hail, or lightning. Researchers from Nvidia, NERSC, and Caltech report an energy efficiency gain of approximately four orders of magnitude in their surrogate weather forecasting system FourCastNet, compared to the baseline weather model (although with lower skill) [46]. Their implementation relies on neural operators that perform much of the computational heavy lifting in the frequency domain, and make use of fast Fourier transforms (FFTs). Similarly, Google/DeepMind released a graph-based neural network (GNN) called GraphCast [47], and Huawei published its Pangu-Weather model [48] based on a three-dimensional transformer architecture, also showing remarkable predictive performance on mid-range weather forecasts.

3.4 Model bias estimation

In the above, we discussed surrogate modeling, wherein part of the model’s work was delegated to AI. Another level at which AI/ML can be applied is on top of the physical model, post-processing or analyzing its outputs. A good example of this is an approach to bias estimation/correction devised by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). Their numerical weather prediction system uses a data assimilation system called ‘4D-Var’, which performs interpolation in space and time between a distribution of meteorological observations and the estimated model state. This data assimilation process results in some recognized biases, which can be estimated using a deep learning model that was pretrained on ERA5 reanalysis data9 before being fine-tuned (cf. Section 2.16) on the computationally expensive integrated data assimilation system [49]. Their results showed a reduction of the temperature bias in the stratosphere by up to 50%. A related application of this idea can be found in studies of dynamical systems, under the name ‘discrepancy modeling’. A nonlinear system is partly modeled with physical equations and constraints, and ML is used to deal with the residuals of this model with respect to observed data [50]. A comprehensive discrepancy modeling framework for learning missing physics and modeling systematic residuals, proposed in 2024, incorporates neural network implementations [51].

3.5 Computational stepping stones

AI methods are applied to an increasing number of domains, to come up with solutions that would take far too much time with conventional methods. For example, a DeepMind effort using a model named ‘AlphaFold’ has managed to produce a database of protein structures for over 200 million known proteins [52]. A protein’s final structure is the result of protein folding, the physical process that translates a polypeptide chain into its stable three-dimensional form, which is notoriously expensive to simulate, and even more laborious to verify experimentally, such as through the use of X-ray crystallography. The structural predictions produced by AlphaFold may not be accurate in every case, but the database constitutes a rich resource for identifying interesting proteins, which can then be investigated through other methods. Possibly, an analogous approach could be used in the context of fluid dynamics, cloud formation, etc.

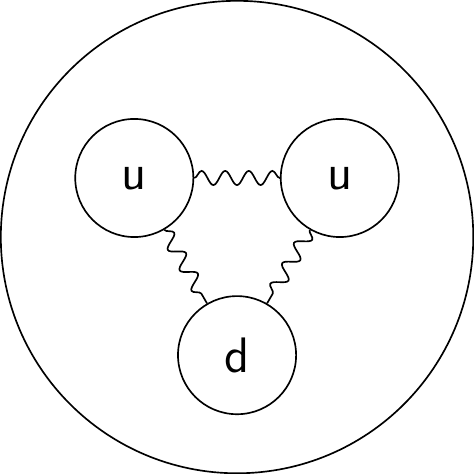

Machine learning is also being used in investigations as fundamental as determining the composition of subatomic particles. A recent study produced computational evidence for ‘charm’ quarks in protons, whereas the standard model only contains the ‘up’ and ‘down’ quark flavors, as per Figure 3.3. This was achieved by fitting parton distribution functions10 to thousands of experimental results, using neural networks [53]. In this case again, AI is a workhorse tool to propel scientific computing forward. Certain classes of problems encountered in the Earth systems may have similar characteristics to those cited above, and could therefore benefit from a similar approach.

Figure 3.3: The established model for the proton contains two ‘up’ (u) quarks and one ‘down’ (d) quark, but no ‘charm’ quarks.

For more in-depth coverage of deep learning applied to Earth Science, and in particular to remote sensing, climate science, and the geosciences, we refer the interested reader to the comprehensive book by Camps-Valls and colleagues [54].